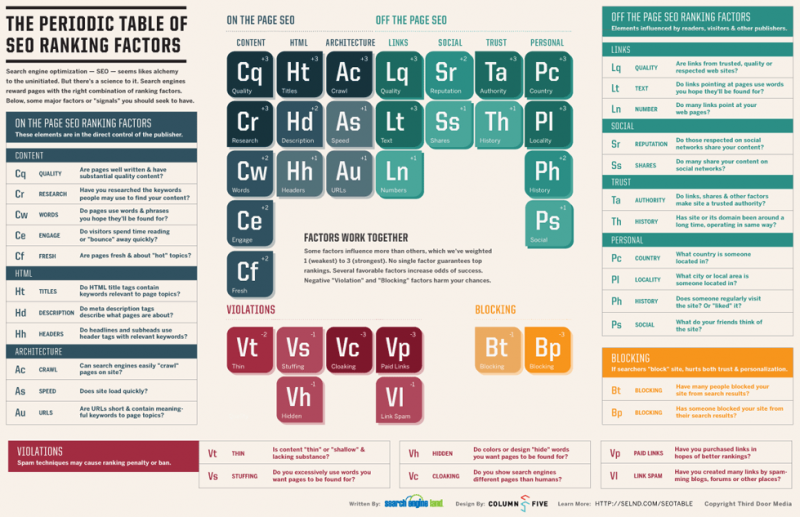

The periodic table of SEO Ranking Factors

While it’s very likely that the BlackBerry PlayBook will receive a native Twitter client in the near future, without an official release date, owners of the PlayBook are left to look to third party developers to fill the gap. At the present time, only two options exist: Tweedless by Mikko Haapoja and Blaq by Kisai Labs.

Tweedless, available free of charge, is a (nearly) fully-featured Twitter client for the PlayBook, with the five icons in the top-right corner of the user interface dedicated to the Home screen (all tweets), Direct Messages, Mentions, Compose Tweet and Compose Direct Message.

What differentiates Tweedless from other Twitter applications – and is the primary manner in which the author describing it – is a Twitter app that “helps you separate the signal from the noise.” In practice, this has a third of Tweedless’s UI dedicated to a “User Filter”, where the selection of one or more of the accounts you are following allows you to view only those tweets. Tweedless keeps track of the number of times you select an account, and over time “automatically sorts who you interact with most” – permanently moving those users to the top of your list for easier selection in the future. The User Filter can be swapped (using the selector at the bottom right) to a Content Filter, allowing you to view only tweets with images, videos or links in them.

The five icons in the top-right corner of the user interface dedicated to the Home screen (all tweets), Direct Messages, Mentions, Compose Tweet and Compose Direct Message. Finally, actions you can take upon a tweet (mention, retweet, direct message or view profile) can be taken dragging your finger to the right upon a user’s profile icon to reveal a set of buttons for those purposes.

Despite the innovative interface, I find using Tweedless an uphill challenge due to three factors:

First, the absence of lists in Tweedless is a huge detractor to my Twitter experience, and is the reason I can’t in good conscience refer to Tweedless as a full-featured Twitter client. I use lists to group the accounts I follow by topic (News, Finance, Software Development) in order to bring context to the tweets I am looking at – User Filters and Content Filters can help compensate, but only partially or awkwardly.

Second, the profile icons pulled in by Tweedless appear to be sized on the small size and scaled up as needed, making the entire application look less crisp than we know is possible.

Thirdly and most detrimentally to the use of the application is that the scrolling motion in the application is somewhat broken. Dragging your finger across a list of tweets moves the list too slowly, a quick swipe upwards or downwards to view the next page of tweets instead sends you down two or three pages worth instead. There is no industry standard for expectations of what a slow or fast swipe will do on a touchscreen device, but the current behaviour is unusable. This, even more than the lack of lists, led me to investigate what the other options were for Twitter clients on the PlayBook.

Blaq ($1.99 USD) comes to the table with a terrific and truly complete list of features: Lists, username auto-completion, profile viewing, in-app website and photo previews and even embed.ly support. The user interface is fairly traditional, with a 50/50 split between the timeline and a compose tweet input box. Icons to view the Home Screen, Mentions, Direct Messages, Lists, Compose Direct Message and Refresh Tweets are located in the bottom right corner and are easily accessed with your right thumb.

While Blaq gets many of the essentials right, one minor and one major fault mar the value of this application. The minor issue is the way that the edge of the tab that slides out as you look at a Web/photo preview or a profile overlaps the main timeline, making a couple of characters in each unreadable. The major issue is that the current version being sold on App World, 1.0.6, is completely missing the Direct Messages, Lists and Compose Direct Message functionality – clicking any of those icons is unresponsive. At the current time, Kisai Labs has not communicated an ETA on a fix via their blog or Twitter account.

Despite having at least half of its expected functionality completely broken, at just $1.99 USD Blaq is for the moment the Twitter application of choice for the BlackBerry PlayBook, especially if you have faith that Kisai Labs will expedite a fix to correct these issues. Having to deal with situations like these is a bit of an indictment of the current state of development on the PlayBook, but it is my hope that the positives of the platform prevail and better options present themselves to its loyal users.

Notes for surviving the apocalypse in style:

Celsias.com – A Refrigerator that Runs Without Electricity

From a family of pot-makers, Mohammed has made ingeniously simple use of the laws of thermodynamics to create the pot-in-pot refrigerator, called a Zeer in Arabic.

Here’s how it works.

You take two earthen pots, both being the same shape but different sizes, and put one within the other. Then, fill the space between the two pots with sand before pouring water into the same cavity to make the sand wet. Then, place food items into the inner pot, and cover with a lid or damp cloth. You only need to ensure the pot-in-pot refrigerator is kept in a dry, well-ventilated space; the laws of thermodynamics does the rest. As the moisture in the sand evaporates, it draws heat away from the inner pot, cooling its contents. The only maintenance required is the addition of more water, around twice a day.

To give an idea of its performance, spinach that would normally wilt within hours in the African heat will last around twelve days in the pot, and items like tomatoes and peppers that normally struggle to survive a few days, now last three weeks. Aubergines (eggplants) get a life extension from just a few days to almost a month.

Here’s my ham-fisted approach to summarizing the article linked to below: New immigrants feel alienated from their surroundings and are thus inclined to watch their children like hawks. This keeps the first generation of immigrants in line, but we then trend back towards the mean afterwards as their children integrate better into the community.

The Walrus – Arrival of the Fittest

An international survey of public attitudes about immigration published in 2009 found that while Canadians have positive feelings overall about immigrants, more than half blame illegal migrants for driving up crime.

What few have bothered to ask is whether there’s any merit to this belief. There have certainly been signs that they should. In Arizona, where a new law makes the failure to carry immigration documents a crime and gives the police broad powers to detain anyone suspected of being in the country illegally — an infraction sometimes called “walking while Hispanic†— crime levels have actually dropped with the concurrent influx of Mexicans.

In fact, the violence of Mexico’s drug war doesn’t seem to have travelled north with immigrants: crime rates in US towns along the country’s 3,200-kilometre southern border are down. In Canada, an overall drop in crime has paralleled the upsurge in non-European immigration since Pierre Trudeau championed multiculturalism in the 1970s. Half of Toronto’s population now consists of those born outside Canada; notably, the city’s crime rate has dropped by 50 percent since 1991, and is significantly lower than that of the country as a whole.

Could it be that immigrants are making us all safer?

Anyone who’s current on technology or business news has seen an article this week like How Wall Street Hustled LinkedIn or Did Bankers Scam LinkedIn Out of Over $130 Million? which discuss the possibility that the LinkedIn IPO partners – Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch and JPMorgan Chase – may have deliberately underpriced the stock in order to score a sweet deal on it for themselves and their favoured investors. Such is the way of Wall Street, it seems.

By chance, today I came across a reprint of Fortune magazine’s 1986 cover story about the tale of Microsoft’s IPO. It’s interesting in itself, but what’s particularly striking is how coolly and calmly Gates and his people negotiated with their IPO partner, Goldman Sachs, to ensure the same little scheme didn’t work on them.

Of course, I could be attributing malice to LinkedIn’s partner banks when the cause for the underpricing could simply be ignorance – how exactly does one justify valuing a social networking company at $9 billion with earnings of $15.4 million last year?

Fortune Magazine – Inside The Deal That Made Bill Gates $350,000,000

…

Gates thinks other entrepreneurs might learn from Microsoft’s (MSFT) experience in crafting what some analysts called ”the deal of the year,” so he invited FORTUNE along for a rare inside view of the arduous five-month process. Companies hardly ever allow such a close look at an offering because they fear that the Securities and Exchange Commission might charge them with touting their stock.

Answers emerged to a host of fascinating questions, from how a company picks investment bankers to how the offering price is set. One surprising fact stands out from Microsoft’s revelations: Instead of deferring to the priesthood of Wall Street underwriters, it took charge of the process from the start.

…

Gates asked Martin to leave while he conferred with Shirley and Gaudette. This was a different Gates from the one who two months before thought $20 too high. ”These guys who happen to be in good with Goldman and get some stock will make an instant profit of $4,” he said. ”Why are we handing millions of the company’s money to Goldman’s favorite clients?” Gaudette stressed that unless Microsoft left some money on the table the institutional investors would stay away. The three decided on a range of $21 to $22 a share, and Gaudette put in a conference call to Goldman and Alex. Brown.

Eric Dobkin, 43, the partner in charge of common stock offerings at Goldman Sachs, felt queasy about Microsoft’s counterproposal. For an hour he tussled with Gaudette, using every argument he could muster. Coming out $1 too high would drive off some high-quality investors. Just a few significant defections could lead other investors to think the offering was losing its luster. Dobkin raised the specter of Sun Microsystems, a maker of high-powered microcomputers for engineers that had gone public three days earlier in a deal co-managed by Alex. Brown. Because of overpricing and bad luck — competitors had recently announced new products — Sun’s shares had dropped from $16 at the offering to $14.50 on the market. Dobkin warned that the market for software stocks was turning iffy.

Gaudette loved it. ”They’re in pain!” he crowed to Shirley. ”They’re used to dictating, but they’re not running the show now and they can’t stand it.” Getting back on the phone, Gaudette crooned: ”Eric, I don’t mean to upset you, but I can’t deny what’s in my head. I keep thinking of all that pent-up demand from individual investors, which you haven’t factored in. And I keep thinking we may never see you again, but you go back to the institutional investors all the time. They’re your customers. I don’t know whose interests you’re trying to serve, but if you’re playing both sides of the street, then we’ve just become adversaries.”

One important workflow to attempt to standardize is the method in which an organization rolls out updates to its production webservers. If you’re making heavy use of Git (and GitHub) in your development environment, it only makes sense to bundle your updates into patch files that can safely be applied and rolled back by someone with no working knowledge of the source code.

To create a patch file out of a Git commit, you’ll first want to retrieve the commit ID that your patch will retrieve data from. The git log command below retrieves information regarding the last 3 commits made:

$ git log -3

commit b29d8f2a0e6ad5595330f62f60b978fbc5696bcb

Author: Sully Syed <sully@yllus.com>

Date: Fri May 13 15:41:05 2011 -0400

The Feed Importer module will hook into Drupal's cron scheduler script and retrieve new

featured articles automatically.

commit 65abfeeea27311effb21a547af99b3427126601f

Author: Sully Syed <sully@yllus.com>

Date: Fri May 13 15:36:01 2011 -0400

Add the Google logo image to the footer directory.

commit 33764e5d9ccd0222ad3d38cc1e77eb8242fb120d

Author: Sully Syed <sully@yllus.com>

Date: Wed May 11 15:45:41 2011 -0400

Fixed the typo that would have made Skynet sentient.

$ git format-patch --help

The git format-patch command allows us to select a range of commit IDs to bundle into a patch. For our example, the range will consist of begin and end with the same commit ID to limit the patch to the one commit:

$ git format-patch -M -C b29d8f2a0e6ad5595330f62f60b978fbc5696bcb~1..b29d8f2a0e6ad5595330f62f60b978fbc5696bcb 0001-The-Feed-Importer-module-will-hook-into-Drupal-s-cron-.patch

The patch file created takes the name 0001-The-Feed-Importer-module-will-hook-into-the-Drupal-s-cron-.patch, which can then be e-mailed or sent by other means to the production staff who will apply it.

Reference: Blogging the Monkey: git format-patch for specific commit-ids

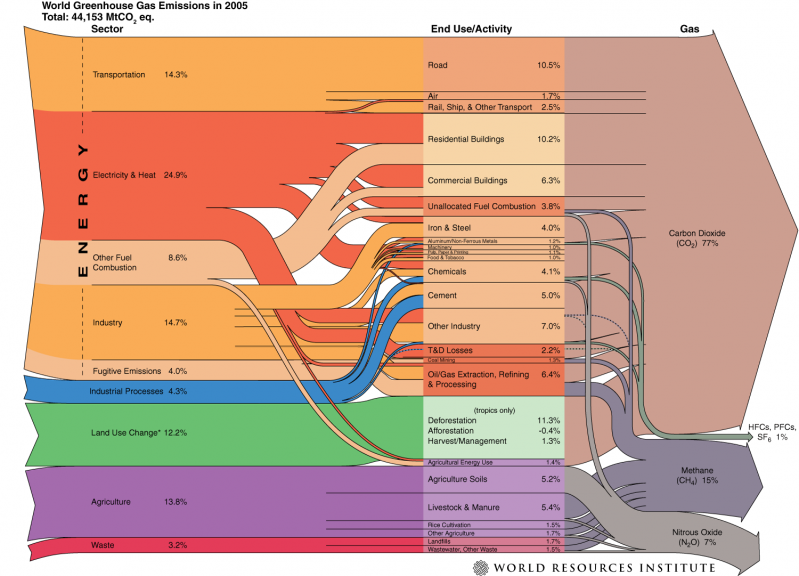

Came across this World Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 2005 infographic by the World Resources Institute.

Via @longreads on Twitter, a summation of what we know about the relationship between cell phones and brain cancer from Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee of Columbia University.

New York Times Magazine: Do Cellphones Cause Brain Cancer?

…

The crudest method to capture a carcinogen’s imprint in a real human population is a large-scale population survey. If a cancer-causing agent increases the incidence of a particular cancer in a population, say tobacco smoking and lung cancer, then the overall incidence of that cancer will rise. That statement sounds simple enough — to find a carcinogen’s shadow, follow the trend in cancer incidence — but there are some fundamental factors that make the task complicated.

The most important of these is life expectancy, which is growing almost everywhere. The average life expectancy of Americans has increased — from 49 in 1900 to 78 in 2011. Several cancers are strongly, often exponentially, age-dependent. An aging population will seem more cancer-afflicted, even if the real cancer incidence has not changed.

But what if we make an “age adjustment†for the population and shrink or expand the cancer incidence to match the changes in age structure? To ask whether cellphones increase the risk of brain cancer, then, we might begin by turning to this question: Has the age-adjusted incidence of brain cancer increased in the recent past?

The quick answer is no. Brain cancer is rare: only about 7 cases are diagnosed per 100,000 men and women in America per year, and a striking increase, following the introduction of a potent carcinogen, should be evident. From 1990 to 2002 — the 12-year period during which cellphone users grew to 135 million from 4 million — the age-adjusted incidence rate for overall brain cancer remained nearly flat. If anything, it decreased slightly, from 7 cases for every 100,000 persons to 6.5 cases (the reasons for the decrease are unknown).

Didn’t seem this coming, but it appears to be an entirely sensible decision. Personal use of workplace-provided devices is bound to creep in, and privacy laws should take that into consideration.

The Globe And Mail – Computer ruling seen as landmark workplace decision

In what is being called a landmark decision, a Ontario court this week ruled that employees have a right to privacy for material contained on a work computer.

The judgment from the Ontario Court of Appeal … agreed with a trial judge that by giving tech devices to employees, along with permission to take them home on evenings and vacations, the employer gave “explicit permission to use the laptops for personal use.â€

The ruling has significant implications for workers who use electronic devices including cell phones for personal purposes – “which is pretty well everyone†– as well as employers who might like to keep tabs on employee use of tech devices, said Frank Addario, of Sack, Goldblatt, Mitchell LLP, who argued the appeal for defendant Richard Cole.

“A big issue here is the tradeoff that employers expect employees to make,†Mr. Addario said. “If they want their employees to be available 24/7 and are giving them BlackBerrys and PCs to contact them outside of business hours, it is inevitable that people are going to use those devices on their personal time as well as business time. That’s an inevitable consequence of asking people to be on call beyond eight hours a day,†he said.

“That means artifacts of personal, private life are going to get left on the electronic devices, regardless of who paid for them,†Mr. Addario said. And the court is saying that employers are going to have to respect that these are the employee’s private property, he said.

…

“I would call the court of appeal finding a seismic shift in the way privacy rights are dealt with in the workplace,†said Daniel Lublin, a lawyer with Whitten & Lublin LLP in Toronto.

“Until now most people generally assumed there was no reasonable expectation of privacy in work computers, and that would extend to work e-mail and Internet use,†he noted. “The court has now resoundingly said that there is a reasonable expectation of privacy in work technology that leaves the office.â€

I’m one of a surprisingly large amount of people that have loaded third-party firmware onto their wireless network router at home. One long standing flaw of the DD-WRT flavour of firmware has been a pair of issues that lead to a momentary loss of connectivity when one’s DHCP server provided IP lease requires renewal.

There are three causes of this issue, and most people will need to address both to solve their connectivity problems:

Let’s address these issues in order. First up: The firmware.

While the official DD-WRT website lists the 2009-10-10 firmware as its recommendation for my Linksys WRT54G v5 router, the forum dedicated to Linksys (Broadcom) routers surprisingly lists this as a build to explicitly avoid. Their alternative solution: Build 14929. (Make sure to take a quick glance at the upgrade procedure before attempting the update.)

Once you’ve logged back into the interface of your freshly flashed router (you should now be running v24-sp2 (08/12/10) micro – build 14929), we can tackle the issue number two. To allow the DHCP renewal messages to be received by your router, you have one of two options: You can disable the SPI Firewall feature completely (Security > Firewall > SPI Firewall), or you can add a rule to specifically allow those messages. Do this by navigating within your router’s interface to Administration > Commands, and entering the following into the Commands fields:

iptables -I INPUT -p udp --sport 67 --dport 68 -j ACCEPT

Press the Save Firewall button to save the rule to be executed whenever the router is restarted.

Finally, you’ll need to disable the DMZ option in DD-WRT by going to NAT / QoS > Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) > Use DMZ and setting it to Disable.

For me, the combination of these three items led to my first uneventful DHCP lease renewal in months. Some of the members of the DD-WRT forums have reported that the second issue was only solved by completely disabling their SPI firewall, so give that a try if the preferred option of adding a rule doesn’t work out.

References: